Yesterday, I pulled a container off a shelf in a cupboard in my kitchen. I filled a pot of water from a faucet and set it on an electric stove to boil. As I opened the container, a familiar smell brought me back to the Wilderness. The container was filled with wild rice that Dave and I harvested late this summer. As I breathed in the rich, grainy smell of the wild rice, memories of our time spent harvesting with four friends were as clear as if it had happened yesterday.

It was mid-August when I smelled wild rice for the first time. As we paddled the Nina Moose River between Lake Agnes and Nina Moose Lake, the shallow water was covered in a swaying, shimmering carpet of green. Actually, carpet isn't quite the right word. The stalks are tall, two to three feet or so—about head height if you’re sitting in a canoe. Like a field of wheat, but green and partially submerged. The smell of the rice was rich and grain-like.

It was mid-August when I smelled wild rice for the first time. As we paddled the Nina Moose River between Lake Agnes and Nina Moose Lake, the shallow water was covered in a swaying, shimmering carpet of green. Actually, carpet isn't quite the right word. The stalks are tall, two to three feet or so—about head height if you’re sitting in a canoe. Like a field of wheat, but green and partially submerged. The smell of the rice was rich and grain-like.

When I say I smelled it for the first time, I don't mean this was my first ever encounter with the wild grain. Rather, this was the first time my nose told my brain, "Ah. That is the scent of wild rice." It took this long for my nose to become accustomed to the scents of the Wilderness. I believe throughout the course of A Year in the Wilderness my sense of smell—like all my senses—became more attuned. I smelled algae from lakes in the late summer. I can recognize the scent of a cedar forest vs. a pine forest. The scent of Labrador tea conjures up thoughts of a pleasant-smelling soap. I even remember the smell of other canoeists we encountered on portages or on the water. They often smelled of soap, sunscreen or bug spray.

The scent of wild rice was satisfying and almost made my mouth water. It is the abundant, water-dependent food source of the area. It is a sacred food of the Anishinaabeg—linked to their ancestral history. Their story of migration is tied to wild rice. I was told that long ago they traveled to northern Minnesota from the eastern United States, and settled in this region once they found a place where food grows on the water.

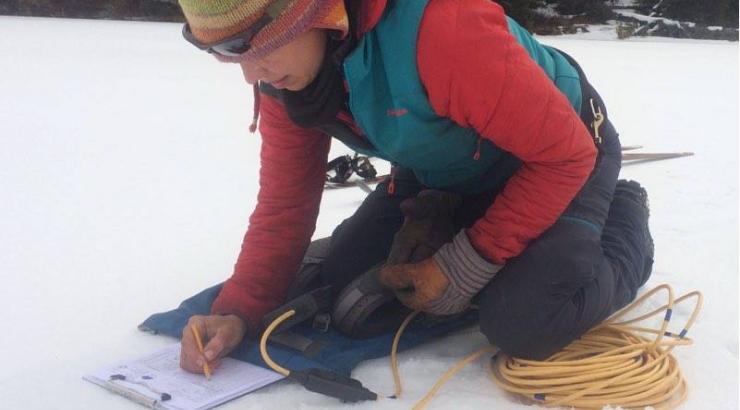

We were honored to be joined by four friends—wild rice harvesting experts—for four days. Read about our experience in a post I wrote for Canoe & Kayak magazine.

That evening I heard two massive birds land in the bay near our campsite. I dropped what I was doing to investigate. Two gleaming white trumpeter swans floated amidst the green stalks of wild rice. I sat on the ground, partially concealed by a jack pine tree to watch the graceful birds. It didn't take long to discern what they were up to. Their black bills grabbed the tops of the stalks, and their long necks curved as they gobbled up the kernels of rice. Over and over, they repeated the process with practiced bobs of their heads. Clearly, it was not just people who depend on the wild rice.

Due to its sensitivity to water pollution, wild rice is the region's canary in the coalmine. The pollutant of concern is elevated levels of sulfate in the water that could result downstream of Twin Metals and other potential copper mines. Sulfate turns into sulfide in the mucky bottom of lakes and streams where wild rice grows. Sulfide is toxic to wild rice because it inhibits nutrient uptake through its roots. If copper mines were built south of the Boundary Waters, the wild rice would be the first plant to suffer.

If we allow these mines to be built, we might as well say goodbye to the wild rice in this region. It is my firm belief that we have no right to allow an activity that produces pollution, which is scientifically proven harms wild rice, to occur within a watershed where it grows in abundance. Rather, it is our responsibility to leave it alone. Keep waters that grow wild rice clean so the Anishinaabeg and others may harvest it next fall, and the next, and the next, and so on. I'd like to give future generations the chance to float in a canoe amidst the head-high stalks and breath in the same aroma I did, to winnow it, parch it, taste it and be nourished by it. This is our responsibility to the place where land and water don't belong to one particular person or company—they belong to all of us.

If we allow these mines to be built, we might as well say goodbye to the wild rice in this region. It is my firm belief that we have no right to allow an activity that produces pollution, which is scientifically proven harms wild rice, to occur within a watershed where it grows in abundance. Rather, it is our responsibility to leave it alone. Keep waters that grow wild rice clean so the Anishinaabeg and others may harvest it next fall, and the next, and the next, and so on. I'd like to give future generations the chance to float in a canoe amidst the head-high stalks and breath in the same aroma I did, to winnow it, parch it, taste it and be nourished by it. This is our responsibility to the place where land and water don't belong to one particular person or company—they belong to all of us.

Want to try some wild rice for yourself? Be sure you get the real deal. The “wild rice” in a box of rice pilaf on the grocery store shelf was probably cultivated in California, where 70% of the wild rice sold in the U.S. is grown. Get hand-harvested, hand-parched, truly wild, wild rice. Check out our trusted source HERE. Enjoy this whole grain that is slightly higher in protein than most others, and is a good source of fiber, folate, magnesium, phosphorus, manganese, zinc, Vitamin B6 and niacin.

Dave and Amy Freeman, 2014 National Geographic Adventurers of the Year, are dedicated to protecting the Boundary Waters from sulfide-ore copper mining proposed on its wilderness edge. In 2014, they paddled and sailed 101 days and 2,000 miles from Ely, MN, to Washington, DC, on the Paddle to DC. From September 23, 2015 to September 23, 2016, the Freemans spent A Year in the Wilderness, camping at approximately 120 different sites, exploring 500 lakes, rivers and streams, and traveling more than 2,000 miles by canoe, foot, ski, snowshoe and dog team. They documented their year and will continue to share their stories on social media (@FreemanExplore, #WildernessYear) and in blog posts. A documentary about their journey, Bear Witness, premieres fall 2016. A book about their year will be published by Milkweed Editions in fall 2017.