The Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness is Minnesota’s crown jewel, and we cannot risk degrading it. Fortunately, Dave and Amy Freeman are helping characterize the water quality of the Boundary Waters. They are using their A Year in the Wilderness expedition to sample water clarity, dissolved oxygen, and conductivity in as many of the Boundary Waters’ 1,175 lakes as they can reach. I recently had the opportunity to meet up with them as they took samples on Rog Lake, and I came away with an appreciation for how hard (and important!) it is to collect data in such remote places.

The Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness is Minnesota’s crown jewel, and we cannot risk degrading it. Fortunately, Dave and Amy Freeman are helping characterize the water quality of the Boundary Waters. They are using their A Year in the Wilderness expedition to sample water clarity, dissolved oxygen, and conductivity in as many of the Boundary Waters’ 1,175 lakes as they can reach. I recently had the opportunity to meet up with them as they took samples on Rog Lake, and I came away with an appreciation for how hard (and important!) it is to collect data in such remote places.

Sunday’s sunshine and warm temperatures were a shock for mid-November, but we basked in the mild conditions. A sapphire mirror stretched away from the landing when we first dipped our paddles in Seagull Lake. We’d driven to the end of the Gunflint Trail the night before and camped at the Trail’s End Campground, where cold stars transfixed us. We had little sense for the rolling hills, exposed rock outcroppings, and remnants of the Ham Lake Fire that surrounded us until the morning broke clear and bright. After being away from canoe country for a little while, it was a perfect reminder of the breathtaking beauty of water, sky, and rock.

We paddled southwest along Three Mile Island and headed for the 20-rod portage into Rog Lake, where I’d arranged to meet Dave and Amy. A light tailwind ruffled the perfect reflection of bare birch and burnt pines. We fell into a rhythm of swinging paddles, quiet conversation, and darting eyes. A bald eagle perched atop a tall wooden spire caught my eye, and I appreciated for the thousandth time the critical role that environmental regulation played in bringing back America’s iconic bird.

We paddled southwest along Three Mile Island and headed for the 20-rod portage into Rog Lake, where I’d arranged to meet Dave and Amy. A light tailwind ruffled the perfect reflection of bare birch and burnt pines. We fell into a rhythm of swinging paddles, quiet conversation, and darting eyes. A bald eagle perched atop a tall wooden spire caught my eye, and I appreciated for the thousandth time the critical role that environmental regulation played in bringing back America’s iconic bird.

Any student of environmental science will tell you that we can’t protect what we don’t understand. When eagles, osprey, and other birds began disappearing across the country, it took a scientist named Rachel Carson to connect the dots between industrial pesticide use, bioaccumulation of toxins up the food chain, and bird declines. Restrictions on pesticide use, the Endangered Species Act, and a whole host of curbs on industrial destruction of the environment followed in subsequent decades.

But what happens when a threatened landscape such as the Boundary Waters is too remote to be studied extensively, especially with limited time, money, and personnel? Without this complete understanding of the Boundary Waters ecosystem’s value -- especially the value of its clean water -- land management agencies would not be able to make a decision that best protects this incredible place. That’s why Dave and Amy Freeman are working so hard to collect water quality data for lakes that the Forest Service and Minnesota Pollution Control Agency (MPCA) simply do not have the time or resources to sample.

When conditions allow, Dave and Amy paddle to the deepest part of the middle of a lake and prepare their instruments. On Rog Lake, they paddled to a point their maps said was 40 feet deep and clocked the position on their GPS device. Dave held the canoe in position while Amy carefully lowered a Secchi disk to measure the water’s clarity, a metric called “turbidity.” The amount of light that penetrates the water is important to track since it influences how well submerged aquatic plants can grow, as well as reflects the amount of sediment, nutrients, and other pollution present in aquatic environments. After the Secchi disk, which was weighted by rocks, disappeared from view underwater, Amy pulled it back up until she could see it again and marked the depth. It was the 56th lake they’d sampled, and the clearest by far.

When conditions allow, Dave and Amy paddle to the deepest part of the middle of a lake and prepare their instruments. On Rog Lake, they paddled to a point their maps said was 40 feet deep and clocked the position on their GPS device. Dave held the canoe in position while Amy carefully lowered a Secchi disk to measure the water’s clarity, a metric called “turbidity.” The amount of light that penetrates the water is important to track since it influences how well submerged aquatic plants can grow, as well as reflects the amount of sediment, nutrients, and other pollution present in aquatic environments. After the Secchi disk, which was weighted by rocks, disappeared from view underwater, Amy pulled it back up until she could see it again and marked the depth. It was the 56th lake they’d sampled, and the clearest by far.

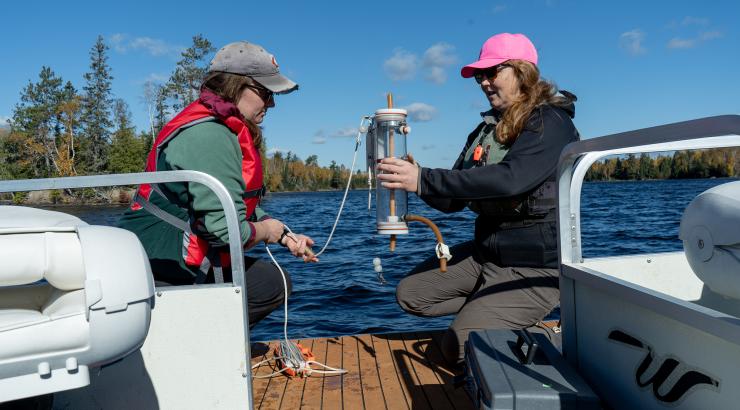

After pulling the Secchi disk back to the surface, Amy prepared a more complex instrument with a probe at the end of a 15-meter cable. She lowered the probe meter by meter and recorded the temperature and dissolved oxygen meter at each stop. As most trout anglers know, cold water can hold more dissolved oxygen than warm water. The oxygen content and temperature can vary with depth, however, and these layers change on both daily and seasonal cycles. By collecting data at varying depths over the course of a whole year, including spring thaw and winter freeze-up, Dave and Amy will able to provide the Forest Service and MPCA with lake mixing data they wouldn’t otherwise be able to collect.

Amy finally hit bottom with the probe and pulled it back into the boat, coiling the electrical cord carefully. The final step was to dip a handheld electrical conductivity meter into the surface of the lake. The reading was higher than other lakes they’d sampled, suggesting that there was a higher concentration of total dissolved ions in Rog Lake than in others they’d tested. Electrical conductivity is an important water quality metric, especially when it comes to considering the impacts of sulfide-ore copper mining, because it reflects the amount of metals present in the ecosystem. Increased electrical conductivity in waters downstream of sulfide-ore copper mines would indicate that they were leaching metals into the surrounding waters, with potentially devastating impacts to aquatic life and human health.

Amy finally hit bottom with the probe and pulled it back into the boat, coiling the electrical cord carefully. The final step was to dip a handheld electrical conductivity meter into the surface of the lake. The reading was higher than other lakes they’d sampled, suggesting that there was a higher concentration of total dissolved ions in Rog Lake than in others they’d tested. Electrical conductivity is an important water quality metric, especially when it comes to considering the impacts of sulfide-ore copper mining, because it reflects the amount of metals present in the ecosystem. Increased electrical conductivity in waters downstream of sulfide-ore copper mines would indicate that they were leaching metals into the surrounding waters, with potentially devastating impacts to aquatic life and human health.

While Amy recorded the electrical conductivity data and put their sampling gear away, I couldn’t help but feel immensely grateful to her and Dave for taking the time to systematically sample the water across the Boundary Waters. Its vast remoteness draws hundreds of thousands of people every year, but prevents researchers from comprehensively documenting the Boundary Waters’ outstanding water quality. By filling in these data gaps, Amy and Dave are ensuring that we have the information necessary to protect the Boundary Waters for this and future generations.

Rachel Garwin is the Campaign's policy director. She holds an M.S. in Natural Resources from the University of Vermont. Every month, Science Desk will include our latest scientific support and share a deeper understanding of the potential environmental impact from sulfide-ore copper mining near the Boundary Waters.