“Late” is something you don’t want to be when heading out on a wilderness trip, especially in winter. There is much to do, daylight is in short supply, and you never know what kind of surprises wait for you out on the trail. You may find deep snow, downed trees across the trail, or a layer of slush sandwiched between lake ice and snow that slows your progress. You might wind up with busted zippers that need to be repaired, dropped mittens or water bottles that must be retrieved, or make a navigation error or two. You could have to re-route around weak ice and there will certainly be animal tracks or sunsets or snow-laden pines which must be marveled at. Anything can happen and all of it takes time, patience, and humble attention to detail. All of that is the reason I love the winter in the wilderness more than any other season.

As the clock struck noon on a day in late January, we were cinching down the straps of our pulk (sled) and clicking our ski boots into our bindings to start our overnight trip into the Boundary Waters. Twenty four hours was all the time we had in our busy schedules for the trip and we had meant to leave by 9 am. After a series of time-consuming events, including slicing my thumb on a can of dog food and nearly fainting at the sight of my own blood, here we were with a mere five hours left before dark and we were just beginning our journey.

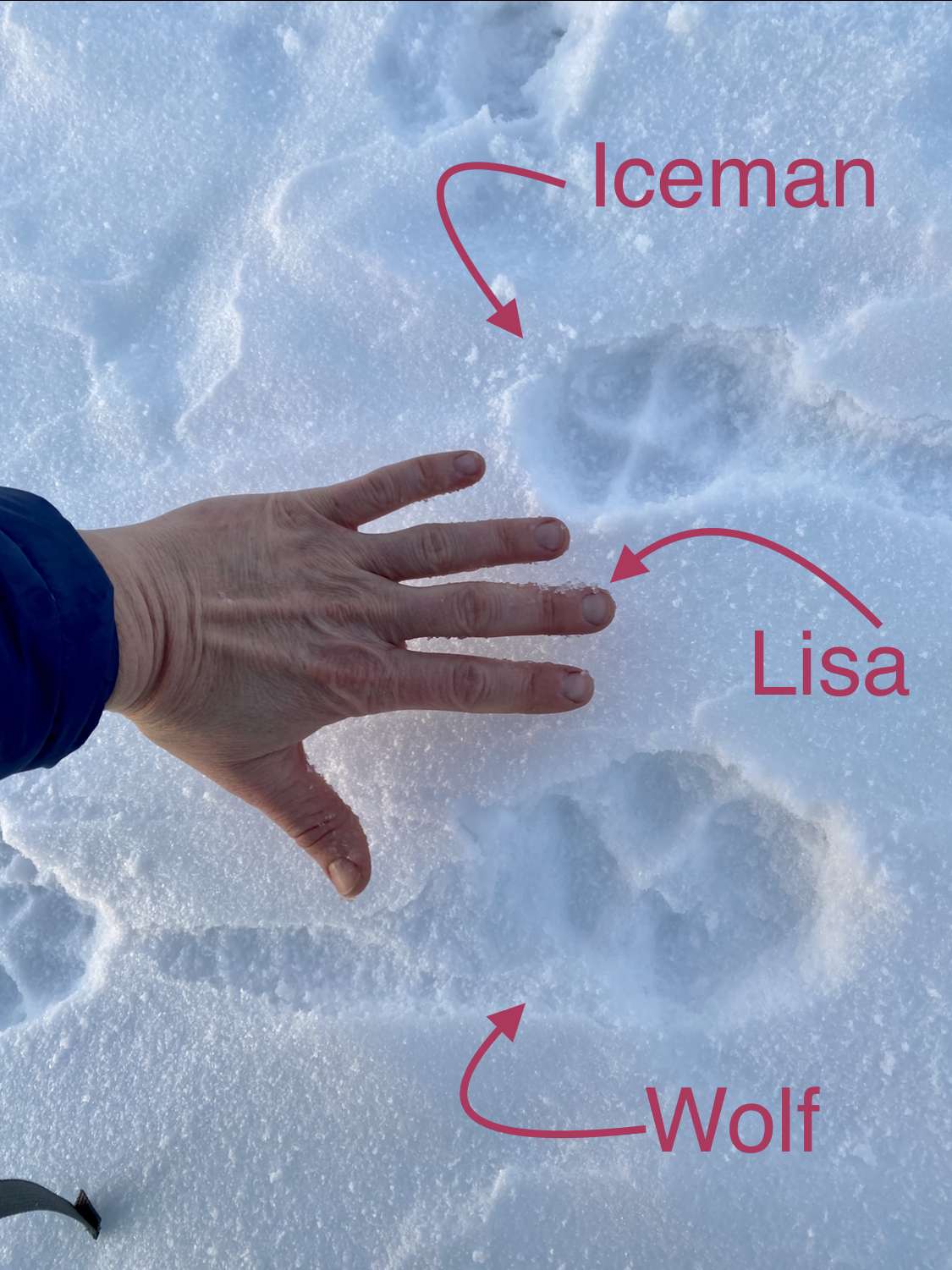

My excitement to sleep on the ground and breathe the cold, clean air all night long soon edged out my annoyance over our tardy start and the first few strides on the frozen lake made my sore thumb a distant memory. My partner, Paul, skied ahead breaking trail and gave our sled dog, Iceman, a target to focus on as he and I followed with the gear and food. I’ll give Iceman most of the credit for pulling the weight. This was Iceman’s second Boundary Waters trip and while it is a little change of pace from the type of running and pulling he did before we adopted him a few months ago, I could tell by his enthusiastic leaps and wild shrieks as we got things moving that he was more than happy to be a part of our team.

We skied hard and took breaks every so often to drink water and have snacks to keep our metabolisms going in the low-20’s temperatures. In typical sled dog fashion, Iceman refused water, choosing instead to eat snow for hydration. We made good time across our entry lake and across the long portage and we paused in mid-afternoon to decide where to camp.

Most of the year, the Boundary Waters rules require you to camp at a designated campsite to minimize impacts, but in the winter you are to camp anywhere but a designated campsite for the same reason.

We had a few good options and chose to cross a small lake into what seemed like a protected little bay on the north side. Paul found our first bit of slush while scouting a route and soaked one of his feet. Because the temperatures were relatively warm and because we were staying warm on the move, he opted to wait until we made camp to change his socks.

Slush, or standing water hiding beneath a layer of snow, is very common on lakes and can be hard to spot. It usually lurks in sheltered bays where the snow is deep but it can often be found out in the middle of lakes too. It forms when lake water seeps up through the many small cracks and fissures in the ice and stays insulated beneath the snow above it. It is typical to find slush after warmer days or a heavy snow when the weight of the snow forces more water up through the cracks, but you can find it on the bitter cold days too. The trouble with slush is, it’s hard to ski through and if the temps are cold enough, it freezes to your skis almost instantly and acts like glue holding you in place until you scrape it off. We hit a big pocket of slush on our way to our camp spot and had to stop to free ourselves. Iceman demonstrated his eagerness to keep moving by tangling himself and me up in his line, requiring a few more minutes and a little more patience before we could continue to camp.

We found a great spot with a slush-free place to build our fire out on the ice where it would have the least impact, a nice spot back among the pines for our shelter, and plenty of good-looking firewood close-by. With about an hour and a half to sunset, our first order of business was to layer up, drink water, eat a ton of cheese and crackers (Iceman got some treats), and change out of our ski boots and into our heavy-duty pac boots for the night. After finishing a Snickers bar each (and a chewy for Iceman), Paul and I divvied up the next set of tasks required for a winter camp.

While Paul found some big, rotten logs to make a base to keep our fire up off the ice and some good, sturdy boughs to make a tripod for cooking, I went in search of firewood. Iceman, having already done his part on the expedition by hauling our gear, curled up and watched us work. Once we were satisfied that we had enough wood for the evening and the following morning, we ate some more snacks, turned on our headlamps, and headed back into the woods to tie up our tarp.

I’ve typically just used a tarp over-head for winter shelter with another tarp underneath for protection from the snow and I’ve found I prefer it to being enclosed in a tent (nylon or canvas) where condensation tends to build and zippers tend to freeze more. I also prefer to sleep without any sort of external heat source, aside from a Nalgene full of hot water I throw in the bottom of my sleeping bag to keep my feet extra warm. With the right sleeping bags, I find this system to be simple, minimal work, and overall more comfortable for me than trying to keep a wood stove going in a canvas tent all night or, worse, falling asleep in a warm tent and waking up in a cold one. This isn’t to knock the way others like to sleep in the winter, there are benefits and drawbacks to any system, this is just the style I like best.

Paul and I each bring two sleeping pads (for me one inflatable, one foam, and two foam pads for Paul) plus two sleeping bags each. I use a 0° down sleeping bag nested inside a bigger 0° synthetic bag. Paul uses two synthetic bags, one rated at 0° and one at 30°. He will often bring a silk or fleece sleeping bag liner as well to have more options. There are lots of ways to make a successful sleeping bag combination that can get you through even the coldest Boundary Waters nights.

Iceman, like all sled dogs, relies on his double-layer fur coat and his instincts to tuck his nose under his tail on the really cold nights. Because he is an Alaskan Husky with a shorter coat and is now acclimated to indoor life with us as opposed to living outside in a big dog yard, we bring a fleece jacket and a wool blanket for him to lay on as extra insulation. If the temps get really, really cold, he’ll be offered a place in one of our sleeping bags. Seeing as the forecasted low was about 11°, that wouldn’t be necessary for this trip.

With the shelter set up, it was finally time to get the fire going and make dinner. Paul worked on splitting a good, dead red pine I found and I got the kindling broken up into some piles to make feeding the fire while cooking dinner easier. I filled our biggest pot to the brim with snow and added some water from my Hydroflask to keep the snow from charring while it heated up. With the pot hung on the tripod Paul made, ready to catch the first heat of the fire and start its process toward becoming our cooking and drinking water, I heaped a pile of birch bark onto our homemade fire pan, added a bunch of dry kindling on top, and fished out the lighter I keep on a string around my neck. Cold lighters won’t ignite, frozen sunscreen and toothpaste won’t squeeze out of a tube, and ice-cold contact solution is not that fun to work with, I’ve been told. For this reason, it’s good to keep those types of things in the warmth close to your body so you can use them when you want or need to.

While I got the fire roaring and kept adding more snow to the pot as it melted down, Paul worked on our Pizza Roll appetizer, my favorite. We filled all of our water bottles (two each) with freshly boiled snow-water and used the rest to boil up the vegetables we had copped back at home where such things are easier. A benefit of winter camping: you can chop vegetables ahead of time (it’s very hard to chop an onion once it’s frozen solid) and bring lots of meat and butter and since you’re camping in a big freezer, none of it will go bad like it might in the summer. I stirred in some ramen noodles and fried up brats as Paul got a hungry Iceman squared away with his kibble, some extra fat, and water. With dinner prepared, water ready, and a fed sled dog, it was now, well after dark, that we were finally able to take a good, long look around and enjoy some peace, some chow, and some good company.

The stars were bright, the moon was nearing full, and the wilderness was still. This is my absolute favorite time to be in the Boundary Waters. It is stunningly beautiful, the chance of running into other visitors is low, the chance of bug bites is zero, and the stakes are high for decision making, problem solving, and survival in general. I love to see the record of who else we’re sharing the trail with in the tracks left in the snow, I love to camp and cook out on the ice, and to admire the way the snow reflects back even a sliver of moonlight. If the moon is full, you don’t even need a headlamp to illuminate your path. I love the sounds you hear in the winter too – the squeak or crunch of snow under your boots that changes tone with the temperature, the more frequent howls of the wolves in their mating season, the groans and cracks of the ice as it forms and shifts on particularly cold nights. I love how the winter can embrace drama and peace at the same time. I love how in winter you must keep moving but then feel such satisfaction in the moments when you can become still.

I should perhaps mention that I spent many years and many hundreds of frozen nights as an instructor for Voyageur Outward Bound School in Ely, MN. My job was to take groups of teens and adults, almost always totally novice and sometimes as their first-ever time camping, on week-long or many weeks-long expeditions in the Boundary Waters. The Boundary Waters is where I really learned the values and skills I most cherish – compassion, stewardship, humility, risk management, group facilitation, and how to hold a paddle and steer a canoe. The Wilderness, even on my own personal trips, or maybe especially on my own personal trips, continues to serve as the ultimate classroom in my life. Time spent in the Boundary Waters has helped me become a more patient, more aware, more capable, and more confident person and I’m so thankful for the opportunities I’ve had to witness such profound beauty and persevere through challenges great and small.

Sitting across the crackling fire from my partner now, with my best little pal curled up next to us, I breathed a sigh of relief at having made it here, back into the Wilderness, back to my home.

We built the fire back up to reheat some water to take in our Nalgenes to bed with us and then let the fire go out as we tidied up the kitchen and covered our wood stash in preparation for the snow that we could already see on its way.

While I brushed my teeth back at our shelter in the woods, the advice I heard on my first winter trip echoed in my mind, “if you put hot coffee in a thermos, it’ll stay hot for a long time. If you put cold coffee in a thermos, it’ll stay cold for a long time.” Sleeping bags act much the same way a thermos does so for that reason, we did some jumping jacks and squats to raise our body temperatures before plunging ourselves into our respective sleeping systems, peeling off and storing our heavy outer layers as we went. The last thing I saw before turning off my headlamp and zipping up the hoods of my sleeping bags, were the big, soft snowflakes falling all around us.

When I later asked Paul what stood out to him about our trip, he said that it’s amazing how you can get the best sleep of your life on the ground in the freezing cold and that it’s incredible how easy it is to leave traces of your visit. I totally agree. We all slept like babies on our 24-hour camping trip, and I’d say we dedicated about 3 of those hours in total to practicing the Leave No Trace (LNT) principles that are Boundary Waters law. You’ll never be able to make a winter camp fully disappear – I mean, eventually the snow will cover all evidence, but come late winter/early spring, it’ll get uncovered and will become an unsightly mess to anyone who might happen upon it - and you can do a lot to minimize your impact. It takes some planning and preparation to be a good steward of this amazing resource we have here in Northern Minnesota and that’s probably why it’s the very first principle of LNT.

After we’d made our morning fire, melted some more snow, cooked our bacon and breakfast sandwiches, and drank our coffee, we began the process of disassembling everything we had assembled the night before. We made sure to burn up all the wood we had brought out for the fire, not leaving any piles behind on the ice, and we even used the shovel that we took along to scoop up the bits of debris and sawdust left over from our wood-processing operation. Pro-tip here: if you clear the snow out of an area on the ice before you haul your firewood out, you can usually clean up the debris in just a few shovel-loads and then fill the snow back in once you’re done for an almost-invisible post-camp aesthetic.

We took apart our tripod and returned it and our base logs to the woods, taking with them the cold ashes that had accumulated on our fire pan. The fire had melted into the ice a bit and it would be impossible for us to get all the bits of ash and coals that were now half-frozen in a sloshy mess, but we scraped up what we could and covered the rest with snow. This would all eventually melt back into the lake, leaving no scars upon the land, and minimal visible impact to anyone who might travel past it later in the season.

I actually find this whole process to be pretty enjoyable. I mean, yes, it’s a chore, but it’s part of the responsibility we take on in exchange for the freedom of the spirit that this place offers us. I’m so grateful for even 24-hours in the wilderness, and I’ll gladly put some of that time back into the place that has given me so much. Would we have liked to stay longer? Definitely. Is 24-hours really worth it? Absolutely. Even if you get a late start.

---------------------------

If you’ve never been winter camping in the Boundary Waters and would like to go, I recommend letting one of these fabulous local businesses show you the ropes: